Main Content

Main Content

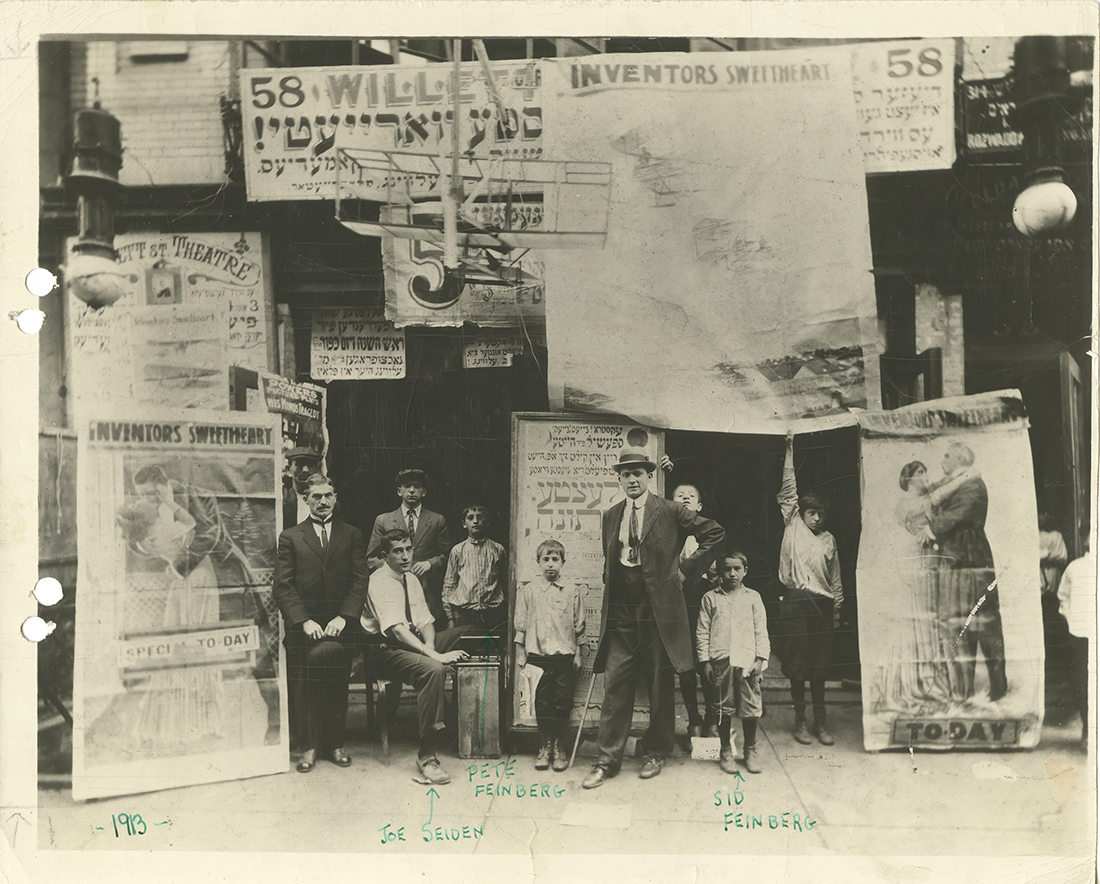

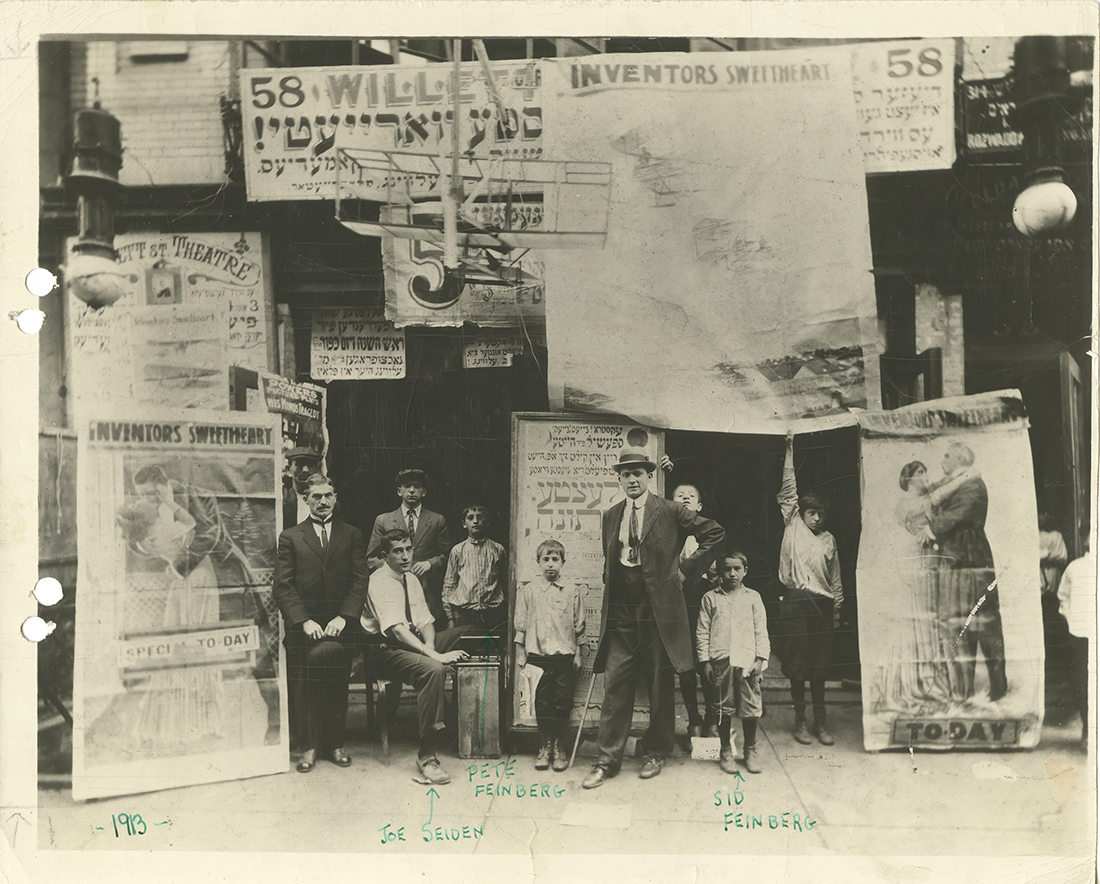

(courtesy of The National Center for Jewish Film, at Brandeis University).

New York’s Lower East Side has long been a destination for immigrants, first Jews from Eastern Europe, then Puerto Rican and Dominicans. As I walk through my neighborhood, I have long had a fantasy of being able to see through walls and windows, as though they were layers of archeological time. Life Forgotten is my attempt to bring not only images but fragments of life from a forgotten past into our world today. What might we learn from radical young women garment workers; immigrants without money or power who in the early years of the 20th century were determined to change their world. But where to begin? For me, a scavenger, of stories, one photograph from 1913, brought everything into focus. Frank Seiden and his sons, standing outside their little storefront cinema or nickelodeon at 58 Willett Street near the Williamsburg Bridge. Mr. Seiden or, as he preferred to be called, Professor Seiden, was a showman from Galicia who had already had a lively career as ‘An Eminent Master of Legerdemain and Prestigitation’ as well as being a recording artist with Columbia Records. Now he made a start in the new medium of moving pictures. For 5 cents he offered everyone, short movies, a song and an ‘extra’.

I soon learned at the beginning of the twentieth century there were more storefront movie theaters on the Lower East Side than almost anywhere in America. At 58 Willett Street one paid one’s admission only to discover, once inside, that the movie theater was upstairs from a rowdy pool hall, so everyone had to shout to be heard. According to the comedian George Burns who, age seven, was employed to raise and lower the curtain, “The movies were made as silent pictures but by the time the Seidens, father and sons, finished with them, they were anything but I guess they figured the competition was so great that they had better add something to get the customers in. So, the three of them, Frank Seiden, Joe, and Jack stood behind the screen and improvised the dialog for the actors.” The audience themselves were far from the passive spectators of today. Quite the contrary, they always had something to say, whether critiquing the action on screen or discussing their lives.

Everyone was jammed up together, eating snacks and candy; Italian, Chinese and Jewish immigrants, breast feeding women, old ladies. Mothers parked their children there while they worked. Cinema was one form of entertainment that was considered suitable for a young woman, since it was not considered proper for them to go to bars or dancehalls. Nickelodeon owners encouraged women’s participation with announcements such as “We are aiming to please the ladies”, “Bring the Children”, “ladies without escorts cordially invited.” Nonetheless risqué movies, jokes and songs were all part of the repertoire.

I want to show that while the politics of social change might seem remote from laughter and entertainment, they are not separate. Life Forgotten focuses on young women watching and reacting to films about women like themselves. How would they have reacted to G. W. Bitzer’s The Broker’s Athletic Typewriter a two-minute short about a stenographer. When her boss sneaks up and grabs her breasts, the eponymous ‘typewriter’ not only not fights him off but picks him by his lapels swings him around, hurls him upside down and bangs his head on the floor. A rare moment of acknowledgement of the sexual harassment that these young women faced on the factory floor. Alternately how might they have might have critiqued melodramas featuring female workers, dying gracefully of consumption like D.W. Griffith’s Song of the Shirt.

One of the principal characters in Life Forgotten is based on a real garment worker and union organizer Clara Lemlich, known, while still in her teens as, ‘a pint of trouble for the bosses’. She and her friends were determined, against all odds to educate themselves. As a young teenager in the Pale of Settlement, Clara defied her parents. To pay for books she sewed buttonholes on shirts and wrote letters for illiterate mothers to send to their children in America. A neighbor secretly lent her revolutionary literature. The discrimination and exploitation that she and her comrades faced when they went to work in America was very clear to them. For one thing they were paid far less than their male counterparts. As Clara put it, “And the bosses, they hire such people to drive you. It is a regular slave factory. Not only your hands and your time but your mind is sold. At the end of a day’s work, we were searched like thieves.” Women were considered ‘unorganizable’ by the male trade unionists who assumed that they would soon be married and leave the workforce. They knew that they could only rely only on themselves.

More than ever the past is not past. The problems of wage theft and the fight for unionization are still ongoing. Right now, immigrants are being demonized and deported by the government, workplaces are being raided. Here, in the Lower East Side amidst gentrification, there are still breadlines.

In a world where thinking is outsourced, entertainment is escape, I want to present another model of being together. In time of trouble, we need comrades to feel less alone, and so I look to the past to find them; intellectuals and working people. Life Forgotten is my way to bring them into the conversation. Those of us who are Jewish, socialist, atheist, anti-Zionists, we too have a history. A great number of socialists and anarchists came to the Lower East Side in the early 20th century and made common cause with struggling immigrants from other diasporas. They give me hope. It is this hope that inspires me to show how they came together to watch movies; to argue,to learn, to laugh and be inspired to work for a better life for all working people.